- Home

- Maiya Williams

Middle-School Cool Page 2

Middle-School Cool Read online

Page 2

Edie Evermint sprinted down the hall, quickly checking her schedule to make sure she had the correct room number before darting into the classroom just as the final reverberations of the gong trailed off. She scanned the tables seeking an open seat and found one in the far corner, next to a girl with a dismayed expression. Edie recognized her from her other classes; this was Victoria Zacarias. The reason why there was an empty seat next to Victoria was that after only one day, it was obvious to everyone that she was a disagreeable person. But since there was no other available seat, Edie took that one. Besides, others might describe her as “disagreeable” as well.

Because this was the first day of school, every teacher had suggested playing the “name game” to help everyone learn each other’s names. In this game a student states his name and some interesting fact about himself. Then the next person has to repeat what the first student said, before adding his own name and a fact about himself. The third person has to repeat the information about person one and two, then add his own name and fact, and so on. But because there were only twenty students in the seventh grade and they all had pretty much the same schedule, not to mention the fact that most of them at least knew of each other from sixth grade at Horsemouth Middle School, by period three all the seventh-grade students knew the names of everyone in their class. By period six the game had lost all of its appeal, if it had any to begin with. By period seven, just to freshen things up, students had started mentioning facts about themselves that were far too personal, some of them downright inappropriate. After all, does anybody really need to know about your toe lint collection? By eighth period the seventh-grade students were ready to revolt.

Edie was possibly the only person who actually liked the name game. She loved to learn things about other people. She made it her business to know everyone else’s business, especially if it was nobody’s business. In her mind the kind of business that was nobody’s business was the very best kind. Edie was a horrible gossip, a sneak, and a snoop.

Altogether there were only nine students in the journalism class, all seventh graders. The rest of the seventh-grade class was scattered among the other three electives: orchestra, art, and computer programming. Sixth graders could choose only between orchestra and art. Though journalism was open to eighth graders, of the ten enrolled in the school, five wanted to do as little work as possible, so they signed up for art. Three were musically inclined and signed up for orchestra. The final two spent all their free time playing video games. They signed up for computer programming.

From her vantage point Edie had a good view of everyone in the class. At the first table sat a boy with curly blond hair who squinted behind a pair of thick glasses. This was Leo Reiss, who was legally blind. Next to him was his best friend, Jory Bellard, a good-looking African American kid who had caused a panic at the end of last year when he jumped off the top of Horsemouth Middle School’s roof with a homemade parachute. He was considered brave, perhaps reckless, and most definitely insane. Margo Fassbinder and Ruben Chao were at the next table. Margo had a bad habit of desperately waving her hand and urgently hooting “Ooh! Ooh!” until the teacher called on her, only to give the wrong answer. Not only was Margo always wrong, she was aggressively wrong. Ruben, on the other hand, was an all-star athlete. He was cute, but unfortunately he was insufferably arrogant and a bully.

At the next table sat Aliya and Taliya Naji, identical twin sisters who looked exactly alike. That would seem redundant, except they really did look exactly the same. Most twins try to distinguish themselves by wearing different clothing or accessories, but Aliya and Taliya extended no such courtesy. They had identical personalities, often wearing the same expression on their faces, with their heads tilted in the same direction. They also finished each other’s sentences. Eerie.

At the table next to Edie’s sat a cowboy. Normally it would be surprising to have a cowboy in one’s class, except that this cowboy had been in all of Edie’s classes, so by ninth period she expected to see him. He wore brown boots, chaps, a vest, and a wide-brimmed hat. A magnificent mustache that curled up at the tips decorated his upper lip. This was Sam Blackmoore, the only student Edie didn’t recognize from Horsemouth Middle School. Perhaps he recently moved to town. She’d have to find out more about him, but her first impression was that he was a major nutter, crazier than Jory, if that was even possible. Either that or he was incredibly stupid. What other reason could there be for wearing a Halloween costume on the first day of school? Sitting next to Sam was Victoria. The scowl on Victoria’s face made it very clear that she did not enjoy sitting next to a rootin’ tootin’ cowboy.

Suddenly the door opened and in walked a thin man wearing thick round spectacles that magnified his eyes. He had a weak, almost nonexistent chin, so that his lower lip made a smooth slope to his clavicle, interrupted only by the large lump of his Adam’s apple. He took his place behind the podium at the front of the room, lightly rubbing his long fingers together like a praying mantis.

“Good afternoon, class,” he said in a high, reedy voice. “My name is Mister. Mr. Mister. I know it’s an unusual name, but please don’t make fun of it. This is Journalism One-A. If you didn’t sign up for this elective, now is the time to excuse yourself.” Nobody moved. Mr. Mister nodded thoughtfully. “All right, all right, it looks like everyone who is supposed to be here is here, or at least everyone who is not supposed to be here is not here. Has everyone been enjoying their first day of school?” Mr. Mister attempted a smile, which seemed a great effort on his part.

“No name game!” the students sang back in a messy sort of unison.

“I’m sorry, you’ll all have to speak louder. I’m wearing earplugs.” Mr. Mister adjusted his glasses. “I’m sensitive to loud noises. My nerves can’t tolerate that … that cannon. Or the gong.”

Jory raised his hand but didn’t wait to be called on. “Why do you work at a school called Kaboom Academy if you can’t stand loud noises?”

“I don’t know where you got the idea that I can’t handle boys. I can handle boys, boys and girls. That’s one of the reasons I’m such an effective teacher. Now let’s get down to business. In this class you are going to learn how to write and produce a newspaper. You will be taught how to find a story, how to research it, how to interview people for it, how to write it, how to edit it, and how to lay out the copy once it has been written. Simply put, you are going to understand what it is to be a journalist. We in this class have the profound responsibility of informing the students, faculty, administrators, staff, your parents, yea verily the entire Horsemouth community, about everything that is newsworthy at this institution. Our goal is to report those things that would be important to our readers without bias and with perfect accuracy.”

Muffled laughter escaped from the students who thought Mr. Mister’s use of “yea verily” was pompous. Victoria, unfazed by the archaic language, raised her hand.

“What about the opinion page? That would be biased,” she pointed out.

“You’ll have to wait to use the bathroom until class is over. You really should take care of that during lunchtime.” Mr. Mister clapped his hands together. “Now. Our newspaper needs a name. Any suggestions?” As ideas were called out, Mr. Mister wrote them on the board. When he was finished, the list looked like this:

Cow Broom Crown Uncle

Dairy Die Mice

Boo Boo Bull Time

Pig Scoot

Antlers Do Best Westerns

“These are horrible suggestions,” muttered Mr. Mister, shaking his head, his fingers fluttering to his neck, searching for the chin that wasn’t there. “Downright awful. Seventh graders, are you? I expected better.”

Jory rose from his seat, jogged to the front of the class, and picked up a marker from the whiteboard. Next to the suggestions he wrote:

Cow Broom Crown Uncle = KABOOM CHRONICLE

Dairy Die Mice = DAILY DYNAMITE

Boo Boo Bull Time = BOOM BOOM BULLETIN

Pig Sc

oot = BIG SCOOP

Antlers Do Best Westerns = ANSWERS TO TEST QUESTIONS. THIS ONE WAS A JOKE, TO GET KIDS TO READ THE NEWSPAPER. GET IT?

YOU CAN’T HEAR WHAT WE’RE SAYING!!!!!

Mr. Mister read what Jory had written and nodded. “Oh. I see. Thanks for clearing things up. Yes, these suggestions are much better. Much better indeed! Well, now that we have our list, let’s take a vote.”

After several minutes of vigorous debate, passionate entreaties, and a few death threats from Ruben, the class reached a consensus. Everyone liked Daily Dynamite the best, for it said everything they hoped the paper would be, mainly explosive. However, there were some obvious problems.

“We can’t write a daily paper,” Leo pointed out. “We don’t have the manpower.”

“You got that right. I am not putting in any extra time,” Ruben said with a yawn.

“But calling it just Dynamite …,” began Aliya.

“… is confusing,” ended Taliya. “People may think …”

“… it’s a magazine about explosives.”

“It’s more confusing for a newspaper that calls itself the Daily Dynamite to only come out four times a year,” Victoria said.

Margo leaped to her feet, waving her hand. “Ooh! Ooh! Guys! I’ve got it! Why don’t we call it the Dynamite Daily?”

“That still has the word ‘daily’ in it,” Victoria growled, leaving out the words “you nitwit,” though that message came through loud and clear. Margo sat down and silently beat her forehead with her fist.

Jory jogged to the front of the room again, grabbed a whiteboard marker, and put an asterisk next to the Daily Dynamite. Then underneath in smaller letters, he wrote, *A Quarterly Periodical. For a moment there was silence, broken only when the cowboy emitted a low whistle.

“By gum, I think that’s gonna work just fine,” the cowboy drawled. Everyone except Victoria joined in with approving comments.

“I think it’s stupid, but far be it from me to disagree with the wisdom of the lowest common denominator,” Victoria said sarcastically. Since nobody understood what she meant, it went by without comment. Then Ruben ran to the board, chose a red marker, and quickly drew a cartoon picture of a stick of dynamite with a sparkling fuse. With a few deft strokes he’d created the banner illustration for the paper and the school mascot.

“Splendid! Excellent!” said Mr. Mister, tapping his fingertips together. “Now all we have to do is divvy up the work. There are many jobs on a newspaper, and there will be plenty for everyone to do, but we need a leader. Who wants to be editor in chief?”

Aliya Naji raised her hand. “I thought you …”

“… were the editor in chief,” Taliya finished.

“The buses won’t arrive until three o’clock. We’ve still got plenty of time,” Mr. Mister assured them. “Now this is supposed to be a student-run paper. The more you do yourselves, the more you’ll learn and the more pride you’ll take in what you’re doing.”

“What he really means is that he’d rather let us do all the work while he plays games on his computer,” Ruben said. Everyone laughed. It wasn’t that funny but no one wanted to get on Ruben’s bad side. Getting on Ruben’s bad side meant being tripped in the hall, having your lunch flipped over, or ending up being shoved inside a locker, so everyone always laughed at even Ruben’s most tepid jokes. Because of the earplugs, Mr. Mister couldn’t hear Ruben. All he saw was the entire class opening their mouths and holding their sides and jerking. He wasn’t sure what it meant.

“Er, gesundheit,” Mr. Mister said. “Anyway, the editor in chief must coordinate assignments among the reporters, read their stories and give suggestions on improvements, decide how the stories will be organized on the page, and answer any letters to the editor. Does anybody want this thankless job?”

Victoria’s hand shot up like a rocket. It accelerated so quickly it broke the sound barrier, creating an isolated sonic boom right in the classroom. Regardless of the hardships, she knew that being the editor in chief of the school newspaper would look fantastic on her resume. Edie’s hand was up next. What better way to know everything that was going on in the school than to be the editor in chief? The third person to raise his hand was Jory, who looked like he might just be stretching.

“All right, three people,” Mr. Mister said. “Let’s hear some speeches. I want each one of you to tell us what your qualifications are for being editor in chief.”

Though she had not been asked to do so, Victoria strolled to the front of the room, her long braid swinging saucily behind her.

“I think you should vote for me because I have an IQ of a hundred and fifty,” Victoria said. “I read at a college level, and I’ve read more books than everyone in this room combined. I don’t need to use a computer to spot spelling or grammatical errors. I own a red pen, and I’m not afraid to use it. I feel comfortable ordering people around, and if you don’t do the job well, I’m perfectly capable of fixing your mess. With me in charge the paper will get done and get done well. That’s it.”

Victoria took her seat to scattered polite applause. “Edie, you’re next,” Mr. Mister said. Since Victoria had set the precedent of speaking from the front of the classroom, Edie followed suit.

“Hello, everyone, I’m the infamous Edie Evermint. Yes, the very same Edie Evermint who last year got two teachers fired at Horsemouth Middle School, wrecked eight close friendships, and spurred ten nervous breakdowns. How did I accomplish those things, you might ask? I’m an expert at gathering information,” Edie explained proudly. “I’ve got an eye for detail, for smelling smoke and finding fires. I’m not held back by scruples or ethics either. I can direct this paper into being the juiciest gossip rag that has ever hit this sleepy town. This is what I do, people: I’m the Michelangelo of muckraking, the Shakespeare of scandal, the Galileo of gossip, the Babe Ruth of rumor mongering, the Einstein of exposé, the Mother Teresa of tittle-tattle! Well, Mother Teresa doesn’t quite fit the picture, but you get what I mean. You want some excitement? You want a paper that people will want to read? Vote for Edie!”

Edie made her way back to her table to the stunned silence of the classroom.

“Thank you, Edie, very compelling,” said Mr. Mister, who hadn’t heard a word of her speech. “Jory, you’re up.”

Jory didn’t go to the front of the class, choosing instead to stand at his seat. His speech was short. “I’m easy to talk to, I’m fair, and I’m not going to bust you if you’re late with an article,” he said. “I’ll just help you get it done. And seriously, guys, are we really going to let the girls run things? Come on.” He sat down.

Mr. Mister told everyone to write the name of the person they were voting for on a piece of paper and put it in the shoe box he was passing around. After collecting the votes and counting them, he announced that Jory Bellard would be this year’s editor in chief. Victoria simmered angrily. She was certain that the only reason she had lost was that she and Edie had split the girl vote and that all the boys had voted in solidarity for Jory. In fact, many of the girls had voted for Jory, impressed by his friendly, easygoing manner. Nevertheless, Victoria abruptly pushed herself away from the table and stormed out of the room, slamming the door behind her.

Edie took the news more gracefully, mainly because she also had voted for Jory. Once she’d thought about it, she realized that she didn’t really want to be in charge; she wanted to be right there in the grime, digging up the dirt. Her new goal was to find the most shocking, jaw-dropping story of the year. But what would it be?

The cannon went off. The first day of school was over.

LESSON 1: WHAT MAKES A GOOD STORY?

The next day Mr. Mister divided up the rest of the newspaper responsibilities. Predictably, Ruben was awarded the position of sports editor. Margo was given the topic of student life. Sam would be responsible for puzzles, games, and comics. Victoria, Aliya and Taliya, and Edie would be the paper’s investigative reporters. The good news was that Mr. Mister had remo

ved one of his earplugs so that he could hear the students more clearly. It made the whole class run much more smoothly.

“We still need a photographer,” Mr. Mister announced after looking over the list. “Leo, why don’t you be the photographer? Do you know how to use a camera?”

“Yes, Mr. Mister,” Leo said hesitantly, “but I don’t think I’m a good choice for photographer. It’s all explained in my file.” Indeed, Leo’s file had a long description about his condition. Leo struggled with extremely poor vision. Whereas a normal person might be able to see an object clearly from two hundred feet away, Leo had to be no more than twenty feet away. He didn’t need a Seeing Eye dog or a cane and he didn’t have to read using Braille, but his vision was seriously impaired.

“I read your file,” Mr. Mister said, shaking his head. “Young man, you can’t let something like this hold you back. I know you think being the photographer would be a challenge for you.”

“Yes,” agreed Leo. “It would be almost impossible.”

“Now, don’t be so negative. Challenges build character. I think you’ll surprise yourself. I bet once you put your mind to it, you’ll rise to the occasion and do a fantastic job. It’s not going to be easy, though.”

“No, sir, it won’t.…”

“You’re going to have to work at it. Work hard. Give it one hundred percent.”

“Yes, sir, but—”

“But you can do it. I’ve got faith in you. You’ve got guts. I can see it in your eyes. Maybe you didn’t know this, but the eyes are windows to the soul. Even though yours are a little crossed, I can see you’ve got what it takes to succeed at whatever you strive for. Don’t let anyone tell you differently.”

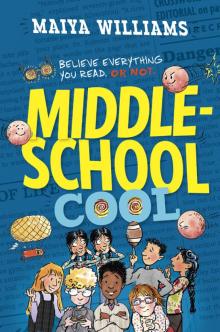

Middle-School Cool

Middle-School Cool